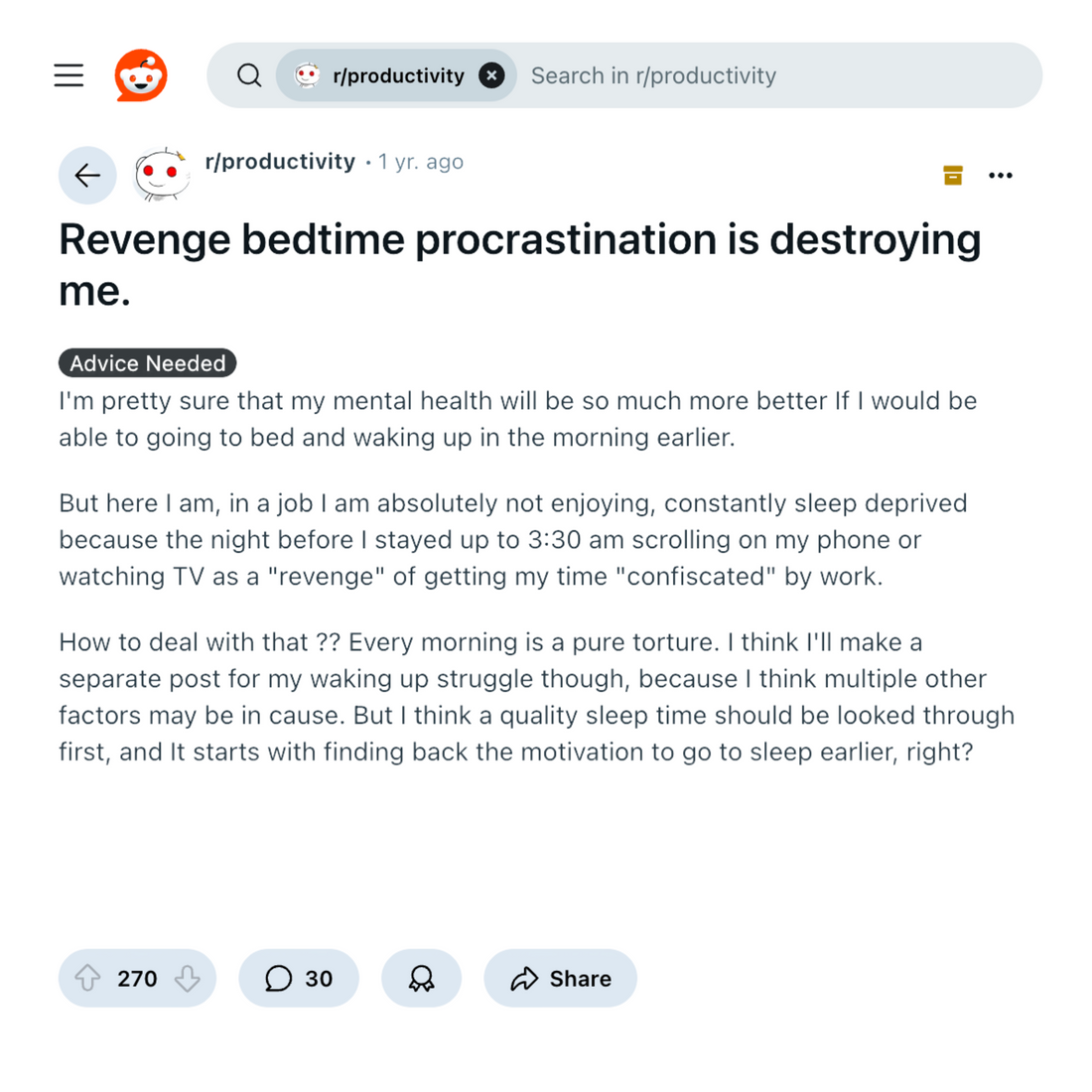

Lots of people joke about binge-scrolling late into the night. It’s become something of a meme: "just one more video," "just one more chapter," or "just 10 more minutes." But there is a neuroscience story behind that delay, and it’s not just weakness. The term "revenge bedtime procrastination" has gone viral - it captures the impulse many of us feel to reclaim a sliver of time in the evening that feels truly like our own, even though you know it will hurt you the next day [1, 2]. In the age of packed days, tight schedules, and blurred boundaries, our brains fight back in the only hours left: nighttime.

Here’s what the science says about how (and why) this happens, and how to break the cycle.

The neuroscience behind staying up late (even when you know you’ll regret it)

-

Dopamine and the brain’s reward system hijack your intentions

When your daytime feels constrained (too many obligations, too few pauses) the brain craves reward. Activities like watching a show, browsing social media, or reading a novel trigger dopamine release in reward pathways. That chemical nudge biases you toward staying awake even when your body is spent, because it influences how we weigh costs and benefits [3]. Sleep loss makes these reward circuits more reactive. In one fMRI study, partial sleep deprivation amplified activity in mesolimbic reward networks in response to positive stimuli [4]. That helps explain why late-night entertainment feels irresistible - your brain is wired to chase the reward now, even if you know you will pay tomorrow. -

Decision fatigue and depleted self-control

Self-regulation is a limited resource. Over the course of a busy day, managing decisions, social dynamics, stress, and executive tasks consumes control. By evening, the part of the brain that says "Go to bed" is weaker. That means the seductive "one more thing" voice often wins. High procrastinators show reduced attention and error monitoring on cognitive tasks, suggesting executive control circuits can falter under strain [5]. -

Circadian misalignment and the drive to “reclaim time”

Your circadian rhythm may not align with your obligations. Evening-type people asked to live on early schedules experience more social jetlag - a mismatch between biological and social time [6]. That misalignment creates stronger urges to reclaim free time at night, even at the cost of sleep. -

Stress, rumination, and emotional arousal

When your mind is still buzzing - thinking through unresolved tasks, upcoming demands, or frustrations - the last quiet hours feel precious. Research shows that nocturnal cognitive arousal and rumination are linked to longer sleep latency and poorer objective sleep quality [7, 8]. The late evening often feels like the only quiet time to process the day, but rumination keeps neural networks activated, making it harder to wind down. Neuroscience finds that even low levels of cognitive activation reduce sleep readiness. -

The paradox of pleasure vs. rest

The irony is that the very behaviors meant to give you a moment of pleasure at night undermine the restoration that would give you more energy, focus, and mood stability the next day. Sleep deprivation impairs decision making and emotion regulation [9]. In the long run, staying up for “me time” steals the very capacity to enjoy your days fully.

A science-based playbook to reclaim your nights

Step 1: Schedule me time in your daytime, before evening fatigue hits

Instead of letting all your downtime line up to bedtime, build short, meaningful breaks into your day. Even 10 to 20 minutes of deliberate personal time can satisfy the brain’s craving for autonomy and reduce the emotional urgency to stay up late.

Step 2: Build a wind-down anchor routine

Consistent cues help the brain know it is time to transition. Choose two or three low-arousal activities (reading, light stretching, quiet reflection) and do them nightly at the same time in dim lighting. Avoid screens or stimulating content.

Step 3: Delay dopamine triggers

Block or limit exposure to high-reward content (social media, video, binge watching, gaming) in the hour before intended sleep. If a craving strikes, redirect to lower-stimulation activities instead.

Step 4: Use "if-then" implementation planning

Prepare ahead: "If it’s 9:30 p.m., then I’ll stop looking at my phone and read for 15 min." Precommitment strategies boost follow-through when discipline is low later.

Step 5: Offload your racing thoughts

If your mind is buzzing, use a quick brain dump on paper or voice note. Offload half-formed thoughts so they don’t loop in your head as you try to sleep.

Step 6: Track and adjust bedtime gradually

If your current habit is midnight, don’t demand 10 p.m. overnight. Move your bedtime earlier in 10–15 minute increments over days or weeks.

Step 7: Use neurotech to support the transition

When your brain is resisting shut-off, tools like closed-loop acoustic stimulation can help. Elemind is designed to do just that, and works like noise-cancellation for your brain. Elemind reads your brainwaves and delivers precisely timed acoustic pulses to nudge your patterns toward sleep.

Why this matters

Revenge bedtime procrastination is not just a bad habit. It is the outcome of modern mismatch: compressed time, high demands, and our brains built to seek reward when deprived. Understanding the neuroscience makes the behavior less shameful and more addressable. Use the steps above, experiment, and bring in tools like Elemind when the night feels too quiet and too tempting.

References

- Kroese FM, et al. “Bedtime procrastination: introducing a new area of procrastination.” Frontiers in Psychology. 2014.

- Herzog-Krzywoszanska R, et al. “General procrastination and bedtime procrastination: how they relate to sleep sufficiency and daytime fatigue.” Scientific Reports. 2024.

- Berridge KC, et al. “Dopamine in motivational control: rewarding, aversive, and alerting.” Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2010.

- Gujar N, et al. “Sleep deprivation amplifies reactivity of brain reward networks.” PNAS. 2011.

- Kowalski J, et al. “Brain potentials reveal reduced attention and error processing in high procrastinators.” International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2020.

- Wittmann M, et al. “Social jetlag: misalignment of biological and social time.” Chronobiology International. 2006.

- Kalmbach DA, et al. “Nocturnal cognitive arousal is associated with objective insomnia measures.” Sleep Medicine. 2014.

- Fernandez-Mendoza J, et al. “Insomnia is associated with cortical hyperarousal as early as adolescence.” Sleep. 2016.

- Krause AJ, et al. “The sleep-deprived human brain.” Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2017.